Masterworks: Highlights of the Collection

This tour features several of the collection's most important works and offers questions to initiate conversation. Click on each image to learn more about the artist and painting.

As you enter the Athenaeum's Art Gallery, a majestic scene of California's Yosemite Valley dominates your view. This is German immigrant painter Albert Bierstadt's The Domes of the Yosemite of 1867, the centerpiece of the Athenaeum's collection. The painting's vast scale is appropriate to the tremendous size of its subject and was intended to amaze audiences on the east coast who had never visited the region.

Let your eye travel down into the valley, following the winding course of the Merced River, and wend your way back up the Royal Arches on the distant valley wall and the landmark profile of Half Dome at the far right. This painting is easily the most recognized work in the Athenaeum's collection, and there is good reason to believe that this end of the Art Gallery was designed specifically for its display.

You can walk up and examine the details of the painting, or back far away to appreciate it's overall composition. If it's open, be sure to climb up the viewing balcony, added in 1882, and experience the painting as Bierstadt himself liked to do. He had similar balconies built in his vast studio in upstate New York. We don't know why Fairbanks chose a monumental depiction of the Sierra Nevada Mountains as the core of an art collection displayed in the midst of Vermont's Green Mountains. What do you think his reasoning was?

To learn more about the Domes Project, click here.

If you turn to your left, you'll find a depiction of the fiery colors of fall in Jasper Cropsey's vivid Autumn on the Ramapo River - Erie Railway of 1876. A young couple stands on a rickety bridge amid the romantic beauty of autumn foliage. The association of youthful love and the brilliance of American fall reflect the nostalgia many Americans felt toward the countryside as both urbanization and industry transformed the nation in the wake of the Civil War. Painted in the year of America's centennial celebration, the work was among Cropsey's most ambitious compositions, as well as the highest priced at $2,500.

After 1876, however, the early group of American landscape painters known collectively as the Hudson River School, of which Cropsey was a leading member, experienced a sharp decline in reputation. The famous Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia placed American and European artists in direct competition, and thereafter young artists sought to cultivate more cosmopolitan modes, such as impressionism, rather than homegrown subjects such as Cropsey's. The painting's title has led to considerable speculation about the subject. No train is in evidence, so perhaps the composition is intended to be a glimpse out of the train's window onto a romantic interlude between country folk. How do you interpret the title?

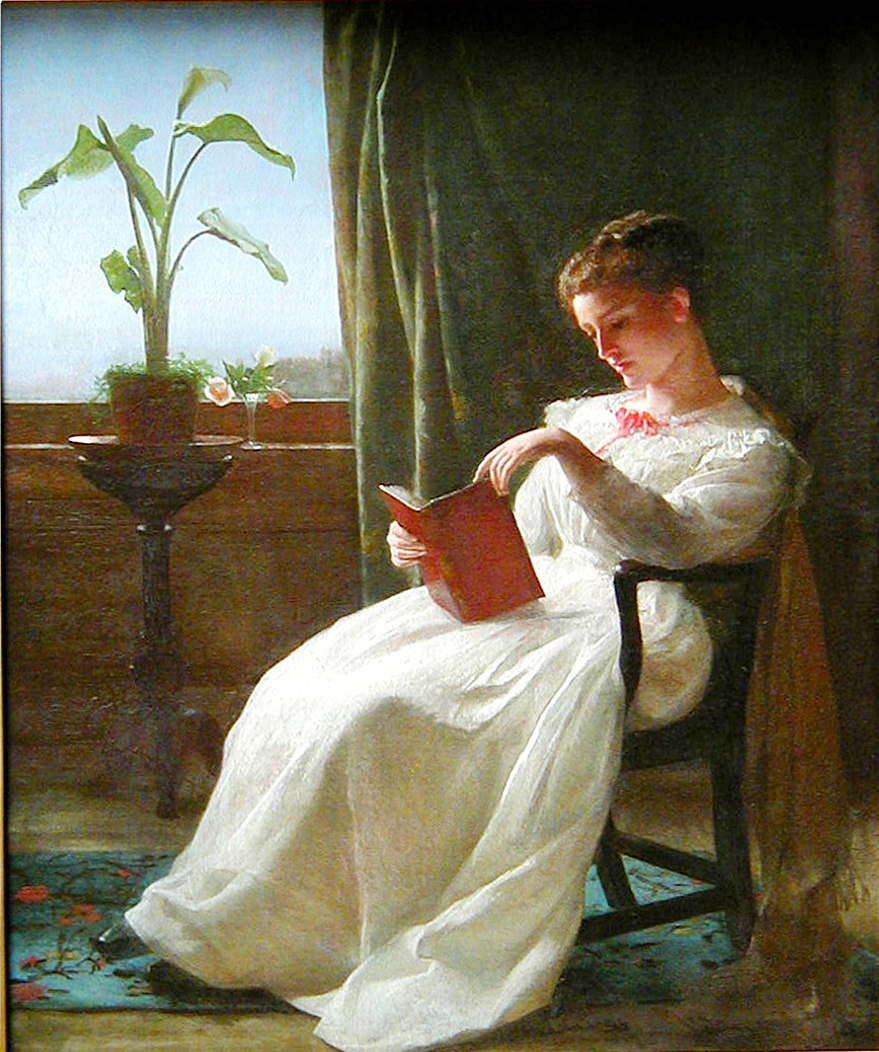

Behind you, you'll find a depiction of a young woman reading by an open window. This is George Cochran Lambdin's Girl Reading of 1872. Take a moment to explore this nuanced composition, the elegant contours of the lily's unfurling leaves, the natural light falling across the girl's face, and the gentle touch of her finger atop the book. The woman-by-the-window motif was very popular during the period. The subject suggests much more meaning than the immediate scene conveys. Reading a book conveys quiet contemplation and the inner life of the mind, while the adjacent window suggests a metaphor for her imagination taking wing.

Girl Reading is one of the most ambitious and complex compositions that Lambdin ever painted, and as such it particularly encourages such speculations. Most of his works are small still life scenes of flowers that bear little meaning beyond their admirable fidelity to nature. Girl Reading, however, intimates a great deal about the subject, associating the girl with the purity of the lily. How are we to understand the three different types of flowers in the scene, though? Living (in the pot), cut (on the sill) and woven (in the rug), flowers abound in the scene, yet their different meanings as symbols are open to interpretation. Looking out the girl's window into the landscape, it is difficult not to imagine nineteenth-century viewers doing the same while sitting in their parlors and looking at landscape paintings by Bierstadt, Cropsey, or our next artist, Sanford Gifford. Their idealized renderings of untouched nature offered a kind of respite from the demands of the working world, a foil for the viewer's imagination and a reminder of trips to the countryside.

Sanford Gifford was fascinated by light and atmosphere. His radiant 1873 composition, The View from South Mountain in the Catskills, portrays a favorite scene of the artist's located near a famous resort hotel, the Catskill Mountain House. Gifford first painted the scene in the midst of the Civil War while home on leave from his service in the Union army in 1863. New York's Catskill Mountains were a popular destination for artists and tourists alike during the nineteenth century, but for Gifford the area was also home. He was raised in neighboring Hudson, New York, and knew the scenery of the region from lifelong experience. Unlike earlier painters of the Catskills, however, Gifford favored an emotive rather than narrative format. Whereas Bierstadt's The Domes of the Yosemite, for example, leads our eye through the scenery along a set path with a string of compositional devices, Gifford's composition focuses on basic masses of color to accentuate a feeling of peace and meditation. The rich sky absorbs our gaze, rather than leading our eye along from place to place within the scene. Mood, however, is a nuanced and personal experience. What mood does the painting evoke in you?

All of the idealism that mid-nineteenth century American painters invested in their works was matched by their sculptor peers. Chauncey Bradley Ives' Pandora, illustrates the classical tale in which a young woman opens a jar entrusted to her care and releases all the ills of civilization. The graceful nude figure is discretely draped to maintain propriety, her rapt attention focused on the jar in her hand. The sculpture is remarkably narrative, her right hand poised to lift the lid. The young woman's tightly bound hair and introspective expression accentuates the stoicism and restraint characteristic of the Greek and Roman sculptures that inspired artists like Ives. Humanity's virtue was, in classical times, perceived to be its control over animal emotion. Balancing that idealism with a distinct element of naturalism, however, the Pandora is a remarkable accomplishment of mid-nineteenth century sculpture that enjoyed long-term popularity. By the time Ives created this version of his Pandora figure in 1875, the original sculpture was already twenty-four years old. To your eye, is this composition more idealistic or realistic? In other words, is she more of a synthetic ideal of womanhood or a portrait of a real person?

Finally, look for a painting of an encampment of Native Americans on the plains below the Rocky Mountains, Worthington Whittredge's On the Plains, Colorado. This panoramic scene of life in the West in 1872 is perhaps less realistic than it appears. Whittredge admired a number of different elements that he encountered along the shore of the Platte River, but they were not all in the same place. In his effort to create a harmonious composition, therefore, Whittredge sacrificed accurate topography. The painting is nevertheless a marvel of balance and form. His technical accomplishment in this work, recognized as among his finest, leaves little doubt to why his peers elected him president of New York's famous National Academy of Design during the mid-1870s. Like Gifford, Whittredge treated the elements of his composition as masses of color and texture, rather than leading the viewer's eye through a narrative. The elegance of his composition derives from balancing elements at varying distances with a remarkable degree of awareness of the abstract weights of different forms. Whittredge was so interested in composition that his figures often seem to play only a secondary role in his paintings. Do you feel that Whittredge had a particular interest in representing Native American culture in this painting? Why?

Self-guided gallery tours are also printed in Mark Mitchell's St. Johnsbury Athenaeum: Handbook of the Gallery Art Collection.